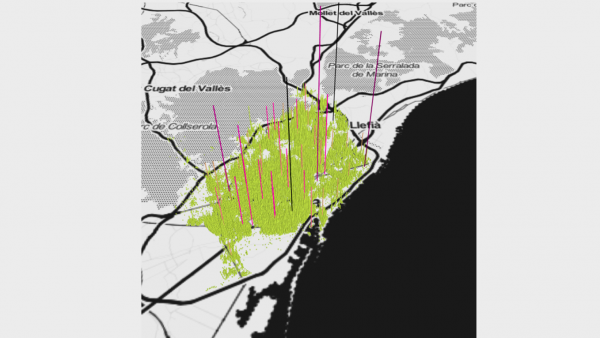

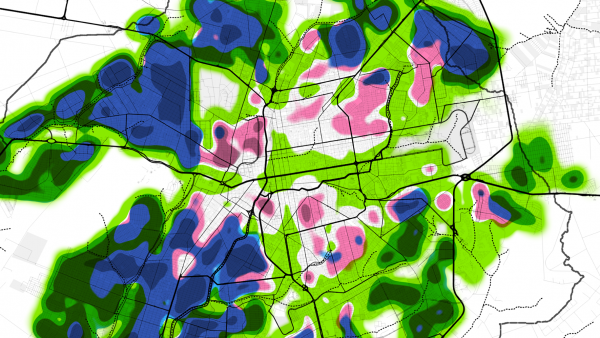

Major environmental problems (such as air pollution or global warming) stem from the need for mobility in cities. Today, we are in the midst of a a systemic change, fuelled by the need of descarbonisation. In recent years, we will shift from a vehicle-centred mobility perspective to slow mobility modes to achieve healthier and more sustainable environments.

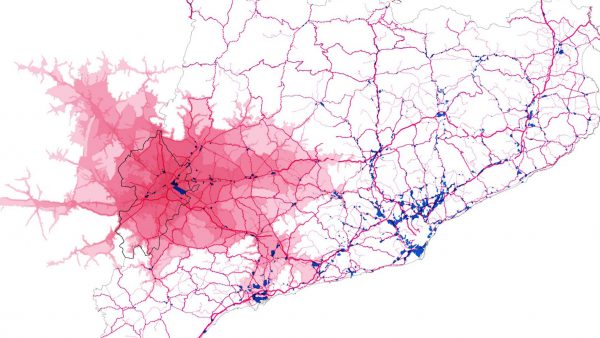

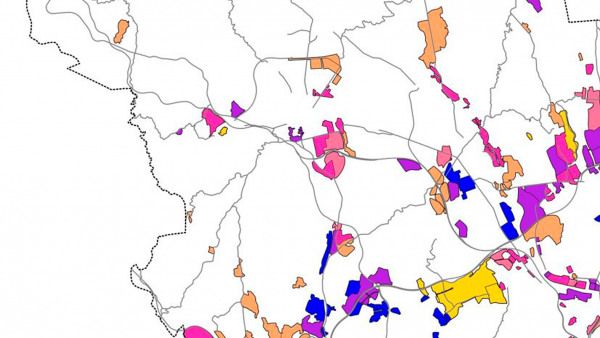

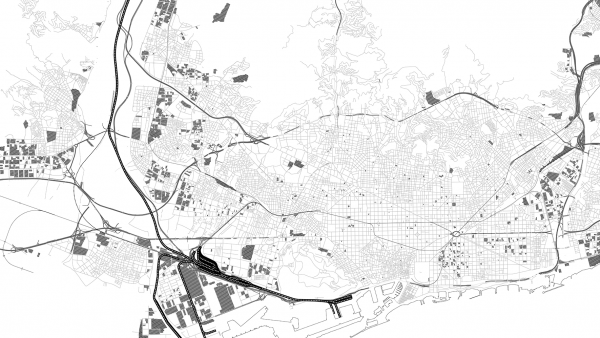

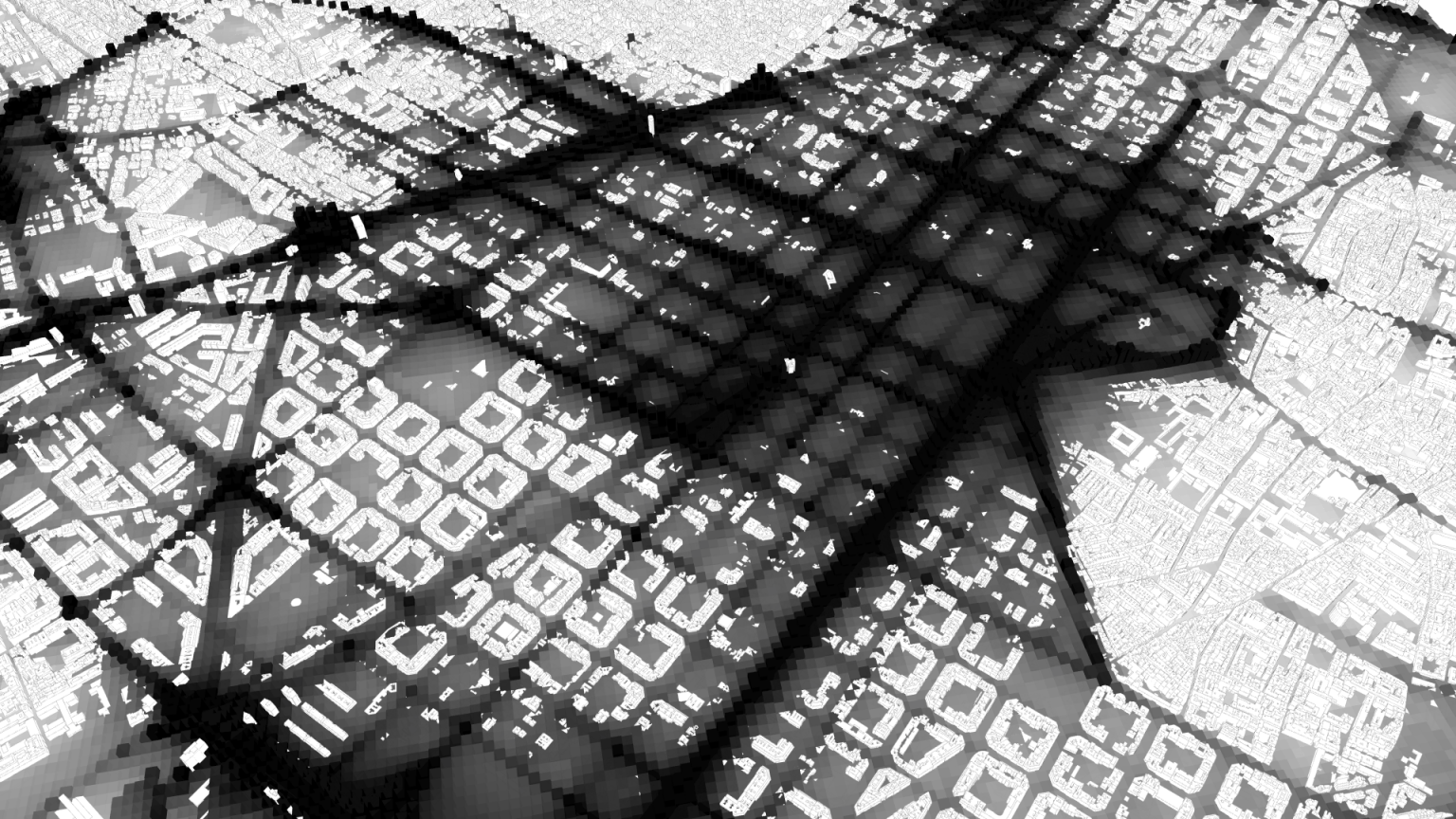

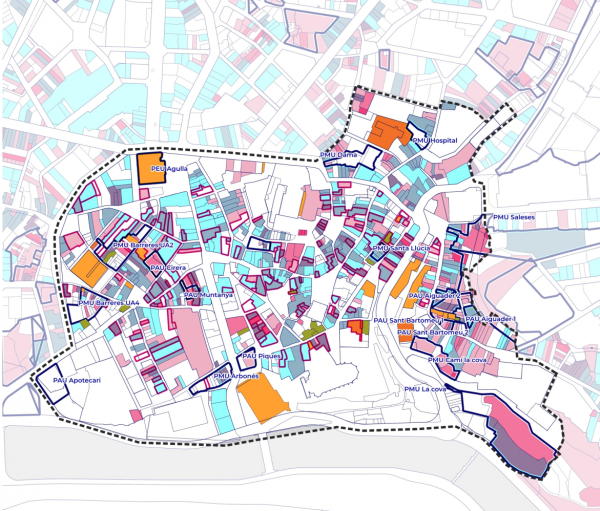

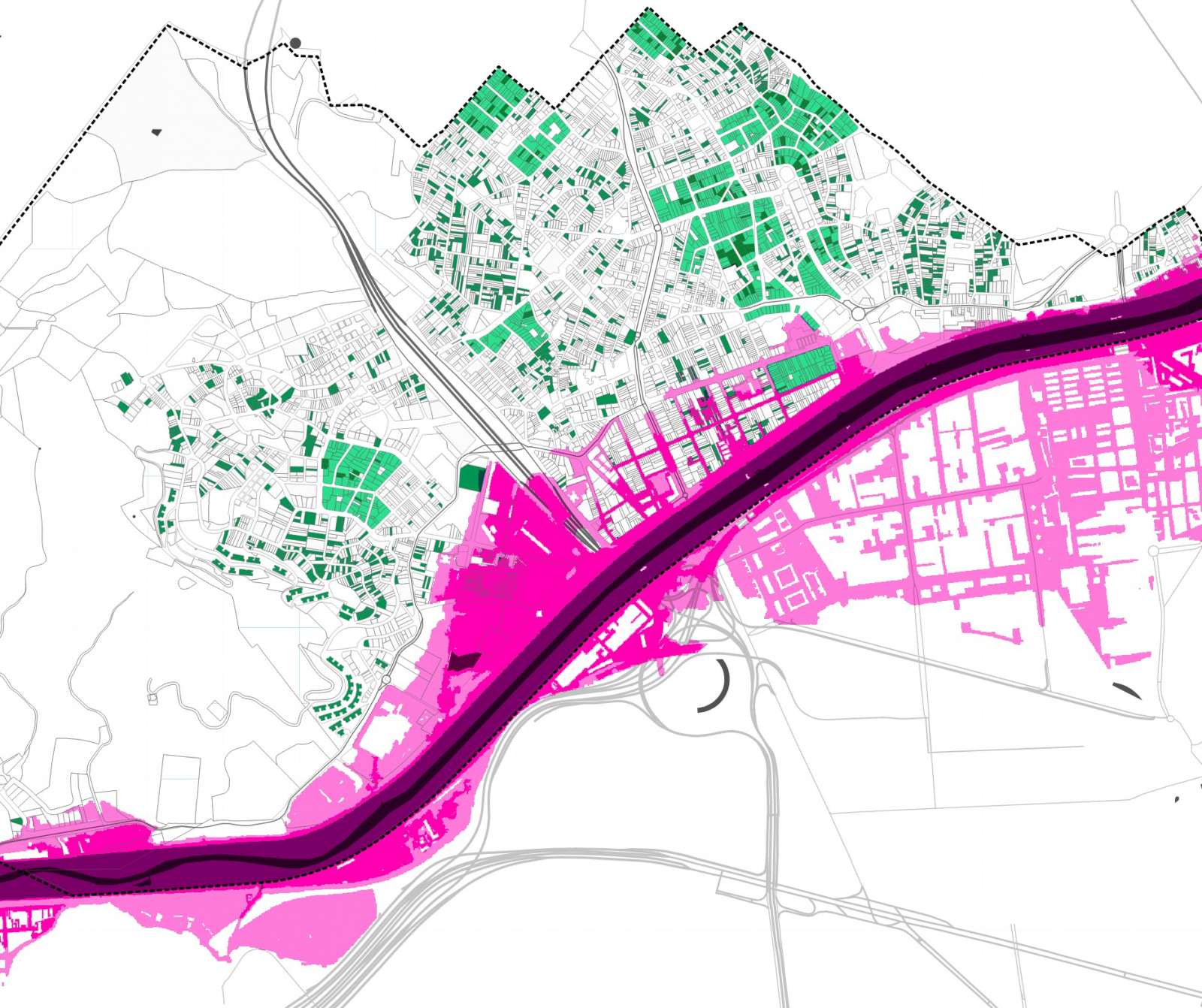

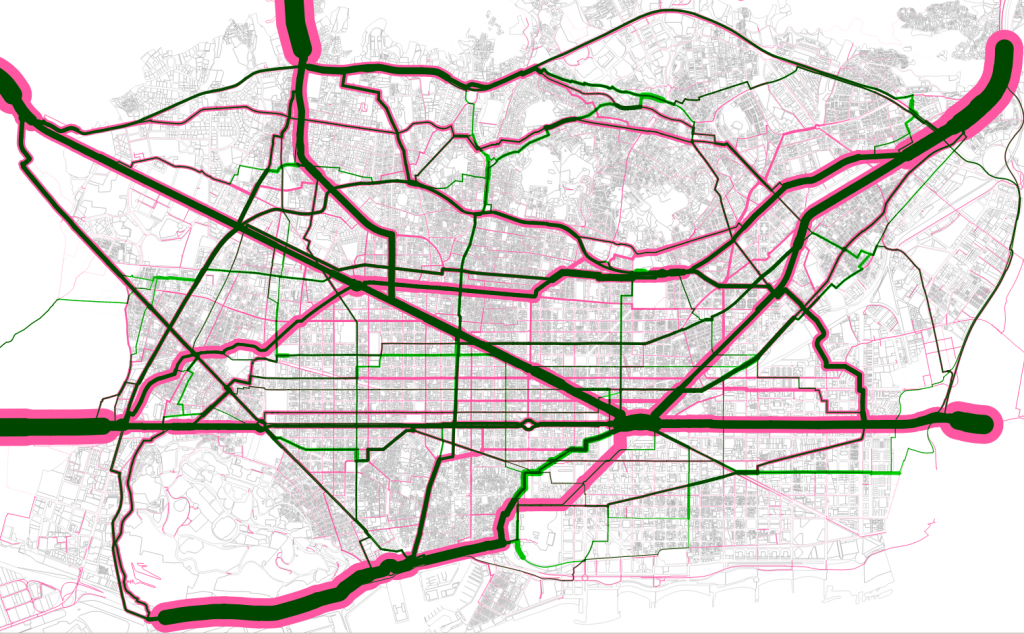

Indeed, the disappearance of private vehicles (as a result of new options tied to mobility as a service) along with improvements in public transportation (network, frequency and mixed-mode), will help us reduce the spaces currently occupied for circulation and individual parking (transforming them into other uses with added value for the city) in favor of new spaces for intermodality and mobility services.

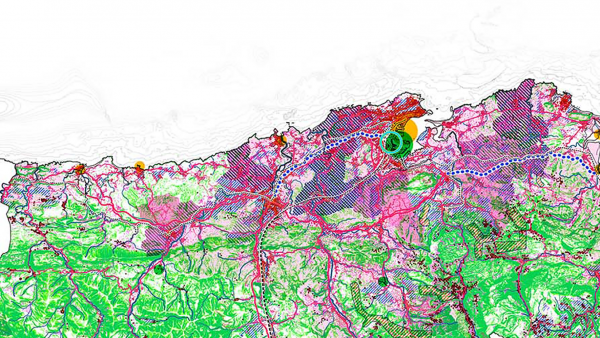

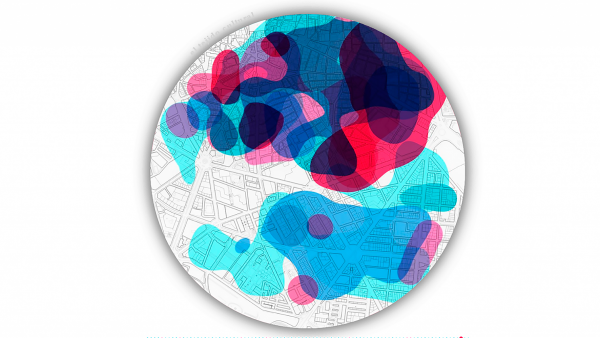

That implies intertwining planning and mobility with an eye to achieving that future and providing nearby access to all the necessary uses for a full life. As a result of this active mobility model (walking and cycling), the city becomes an infrastructure that promotes healthy habits and generates collective health. On the other side, the management of freight mobility is becoming a major issue in urban areas. Offshoring production and storage generates intense internal logistic flows which have been intensified by the emergence of e-commerce, forcing us to address logistics needs inside the city.

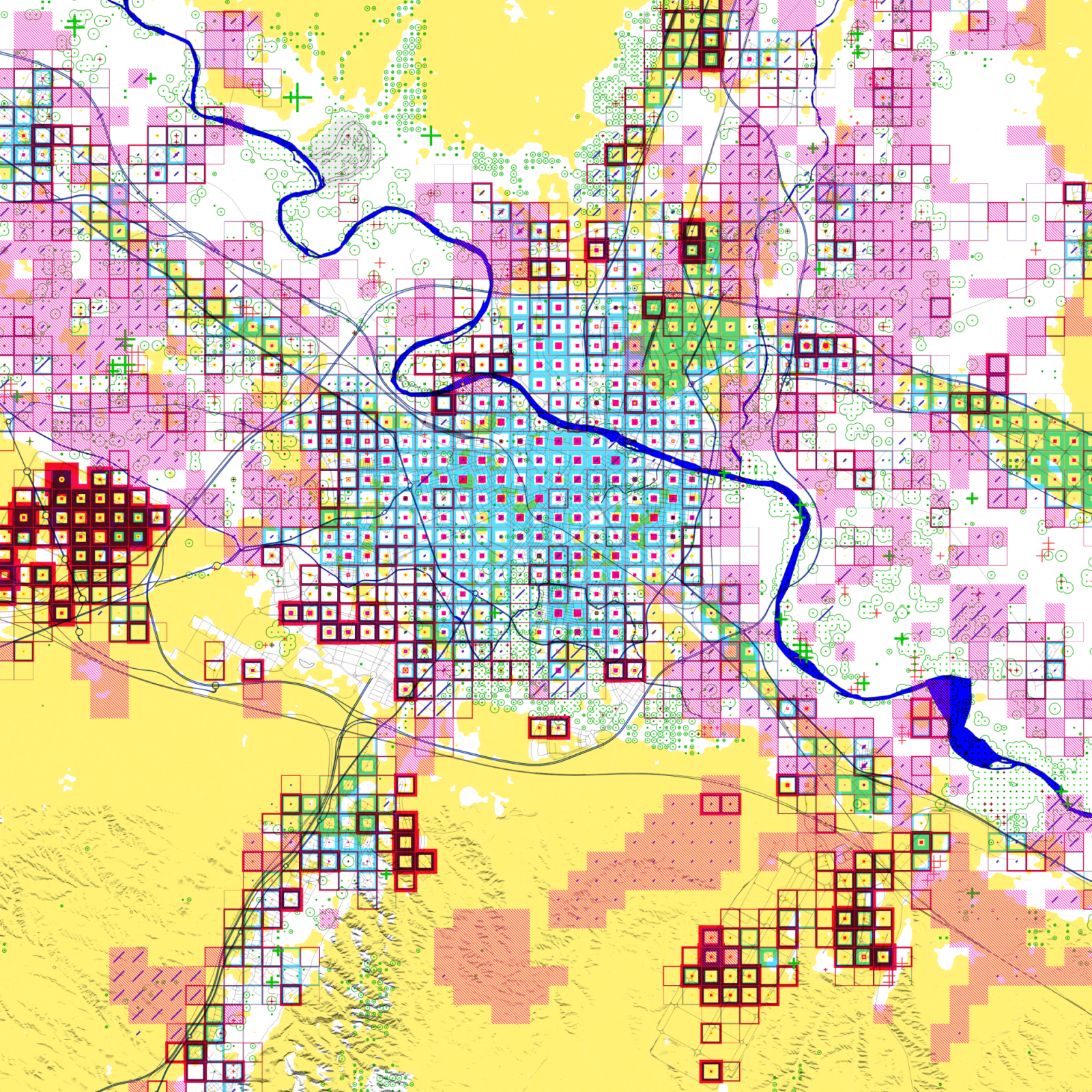

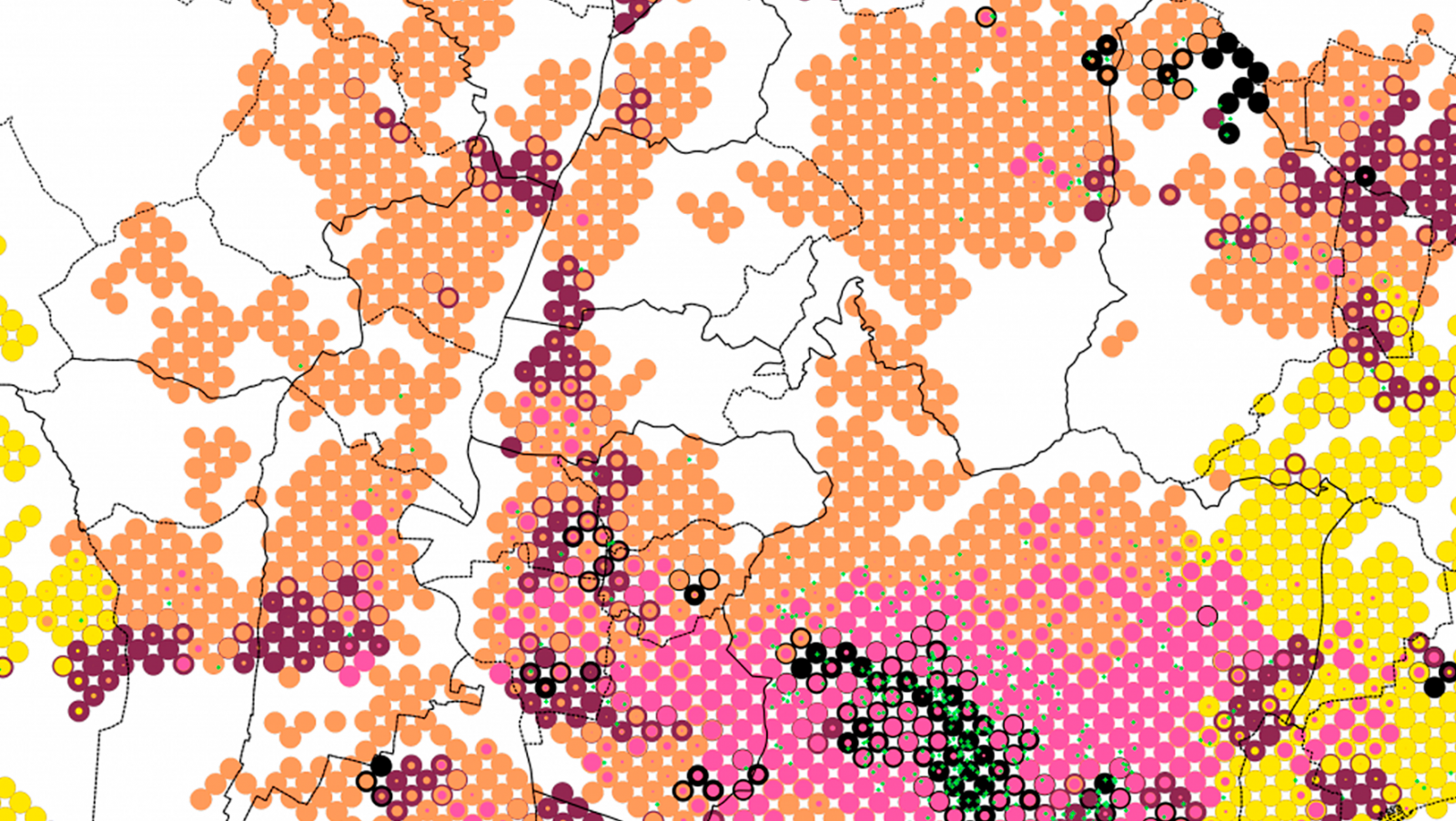

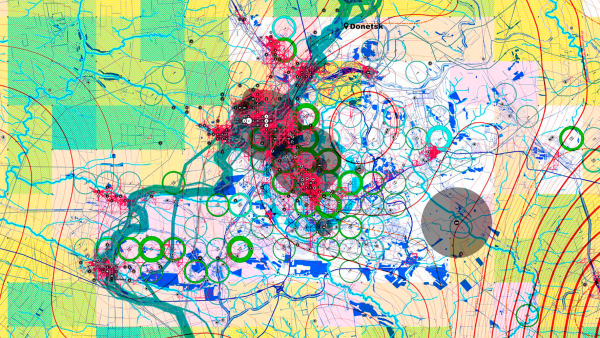

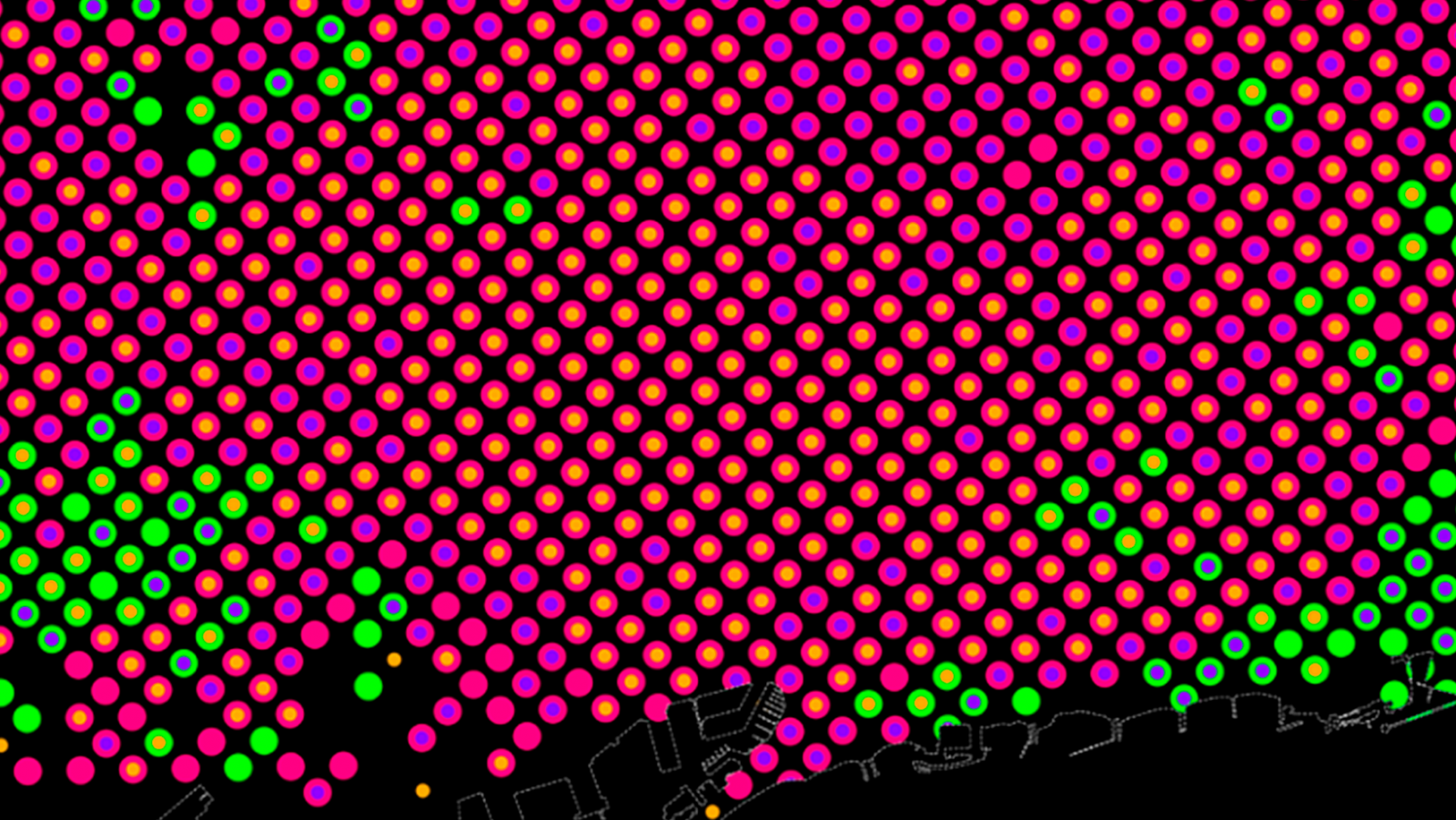

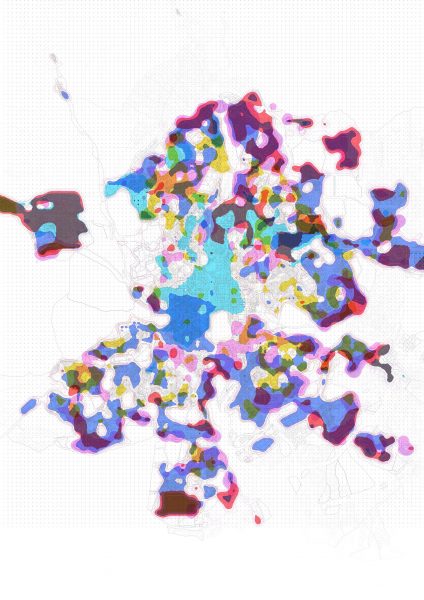

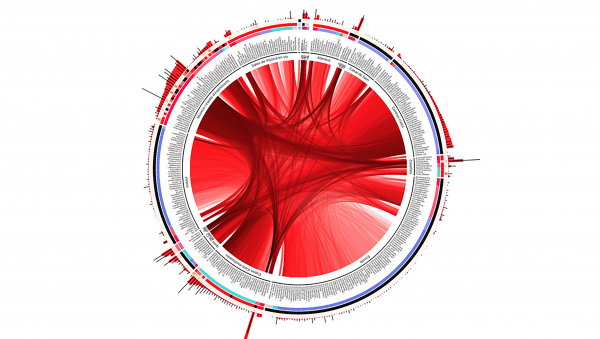

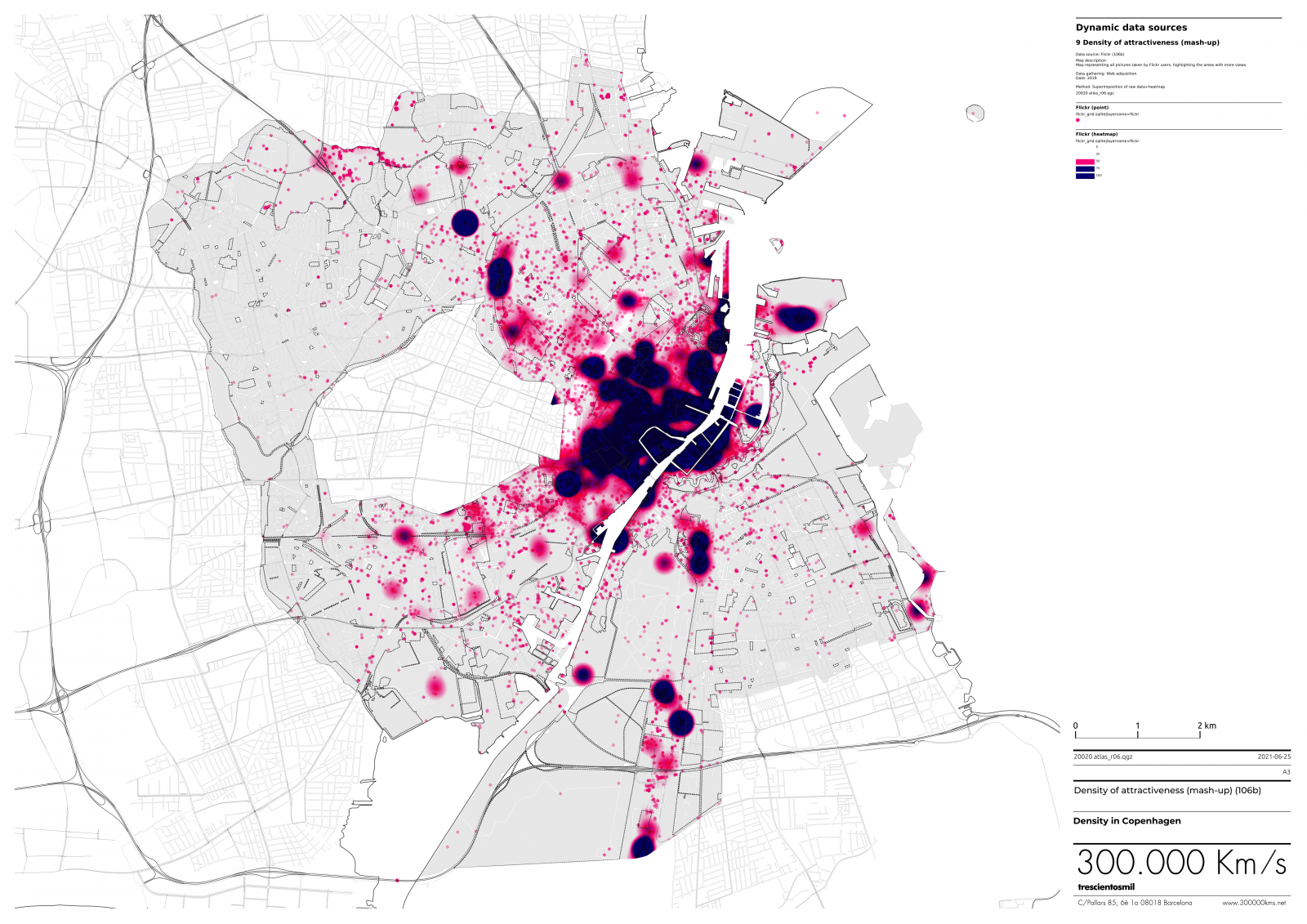

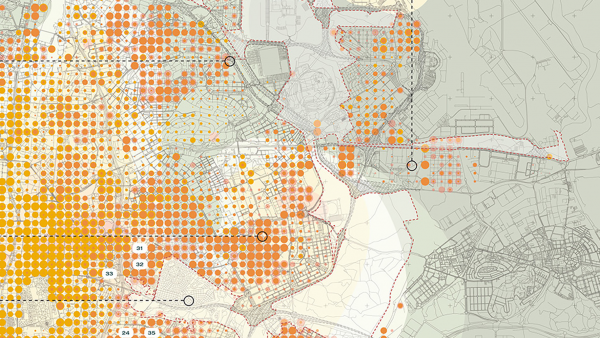

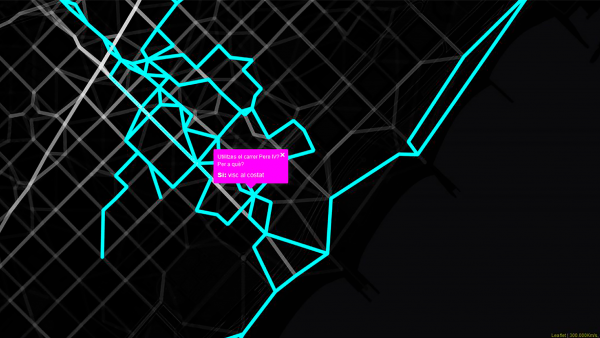

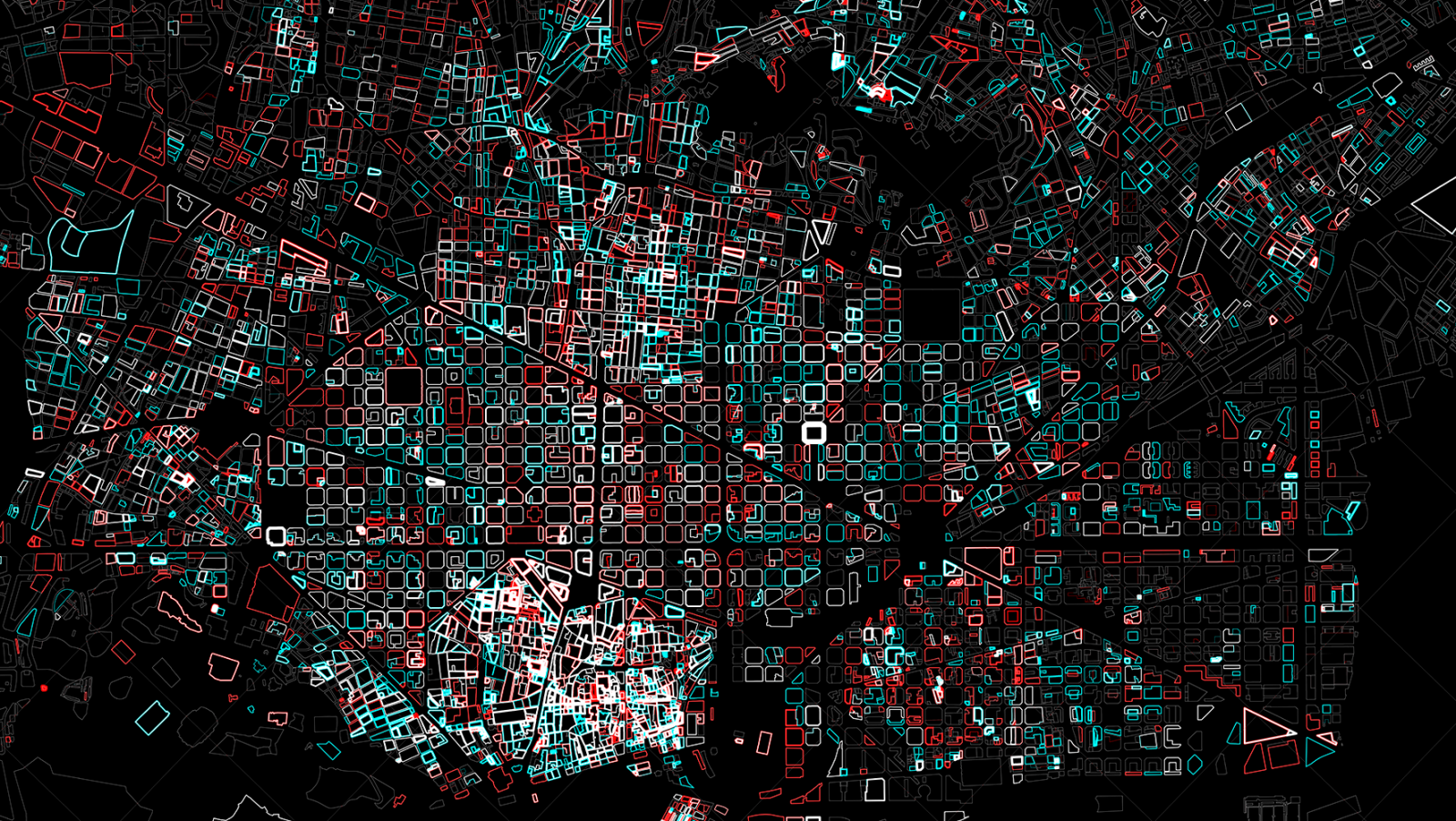

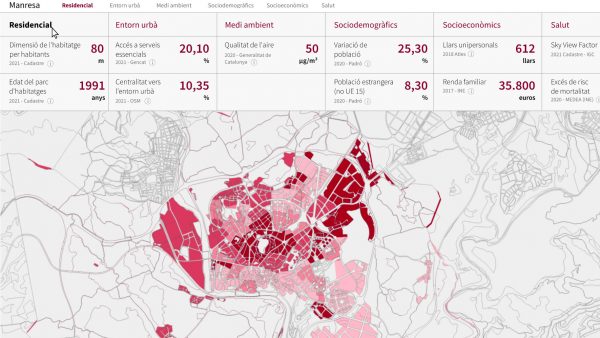

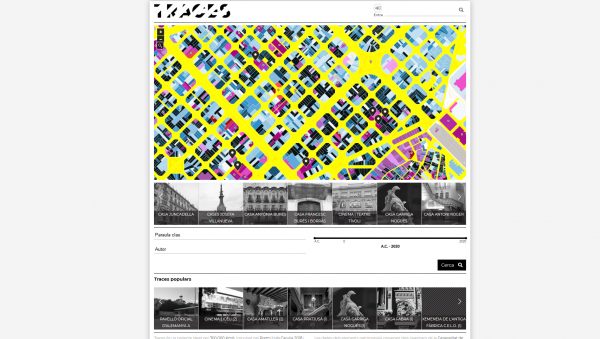

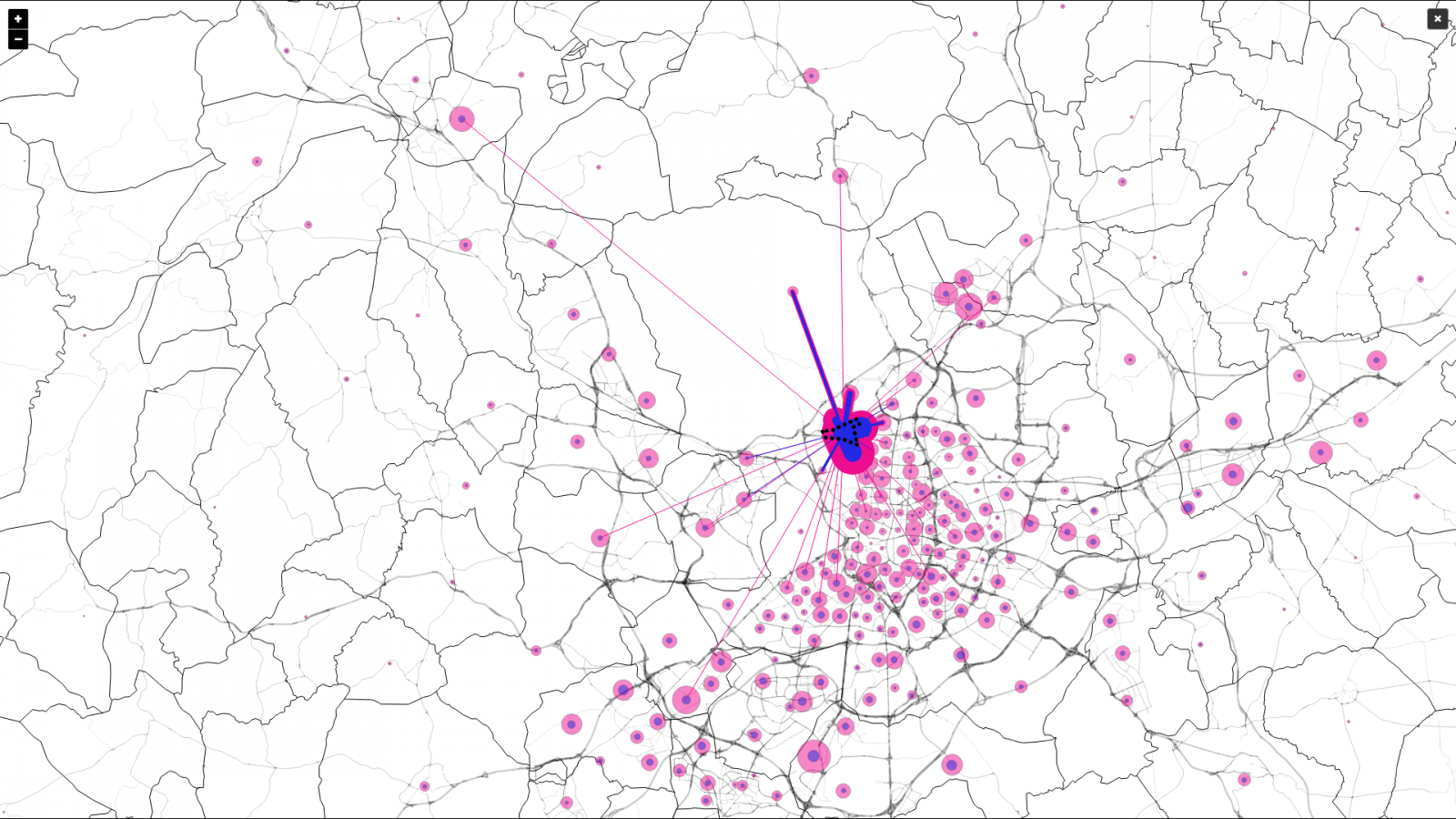

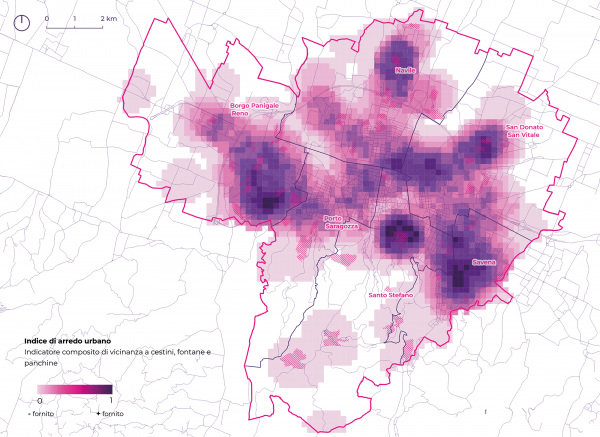

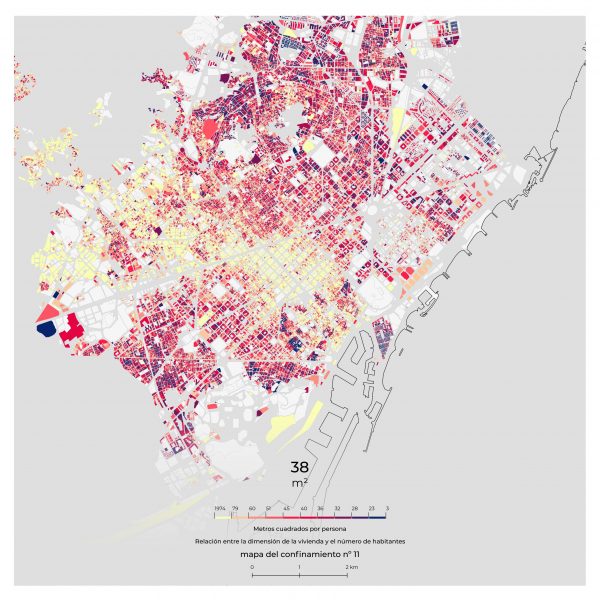

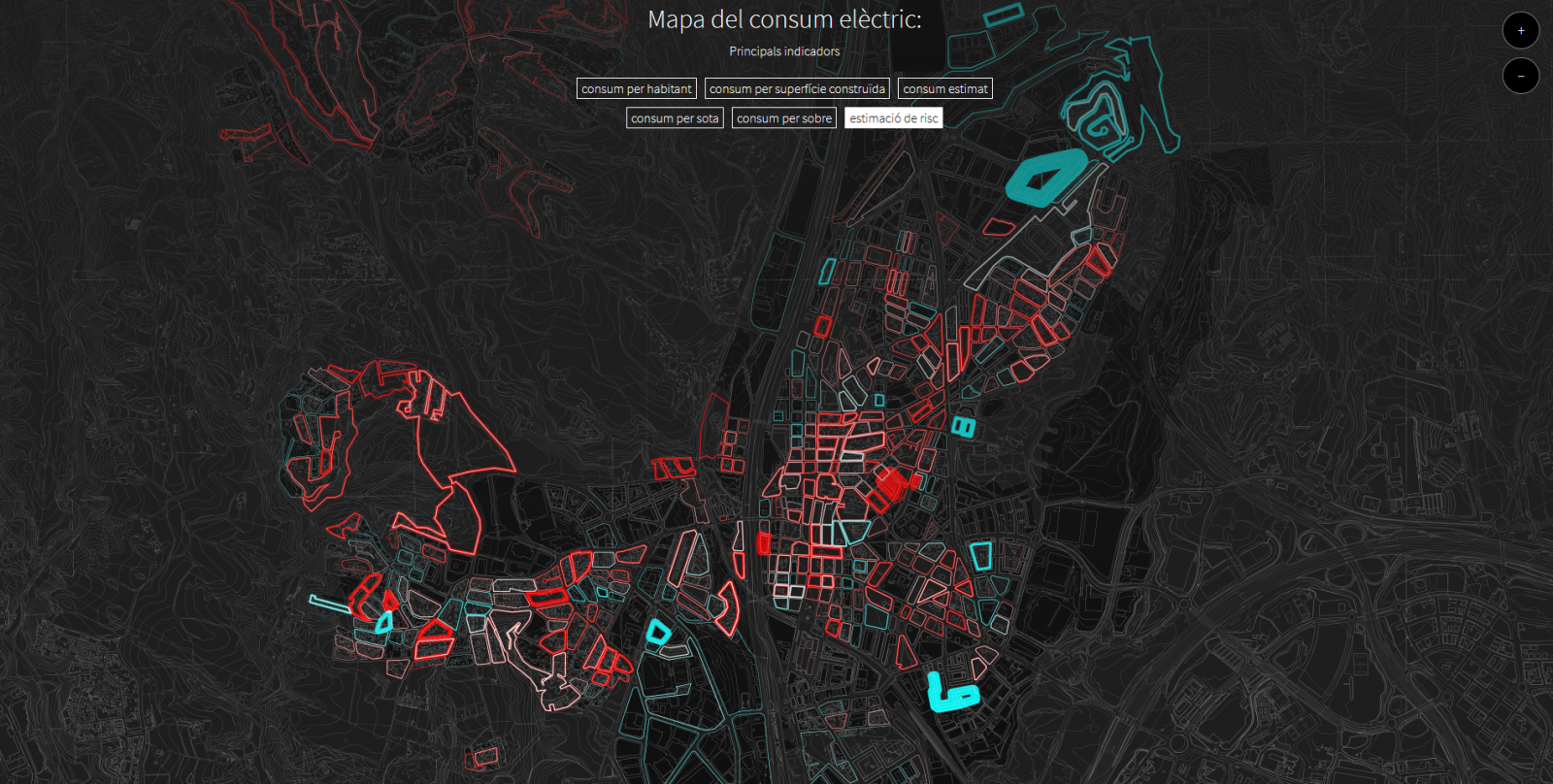

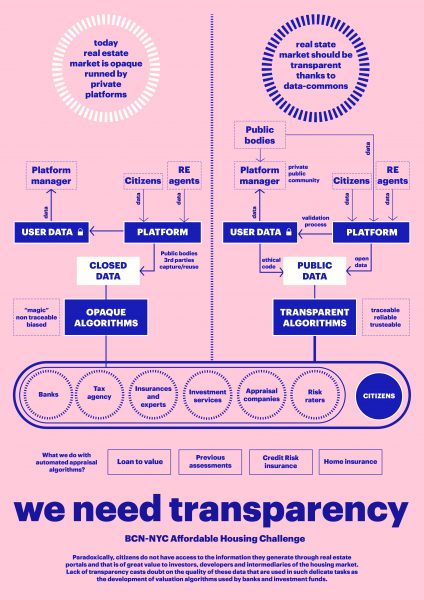

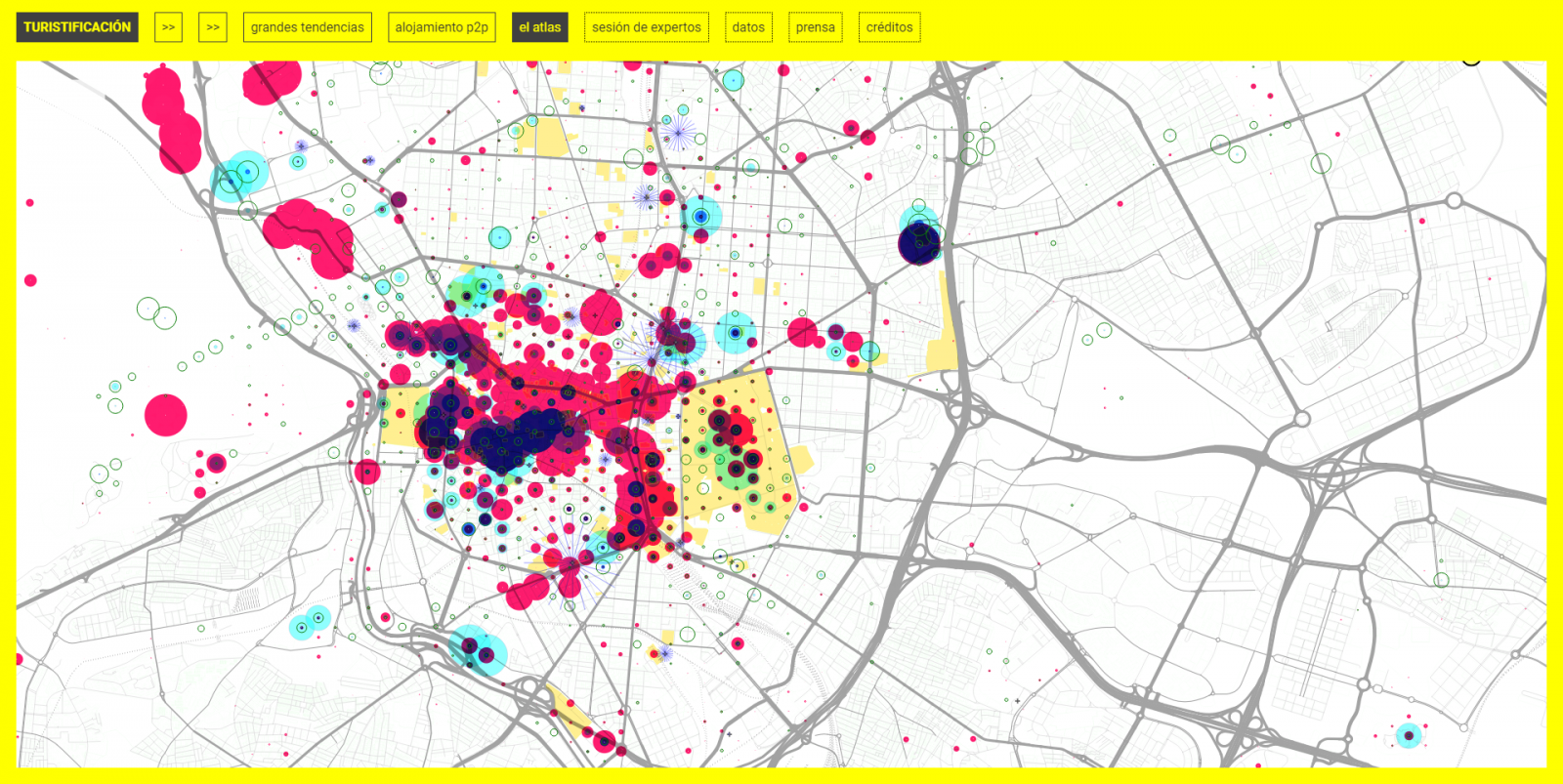

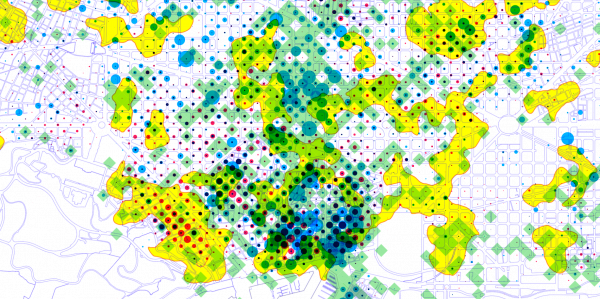

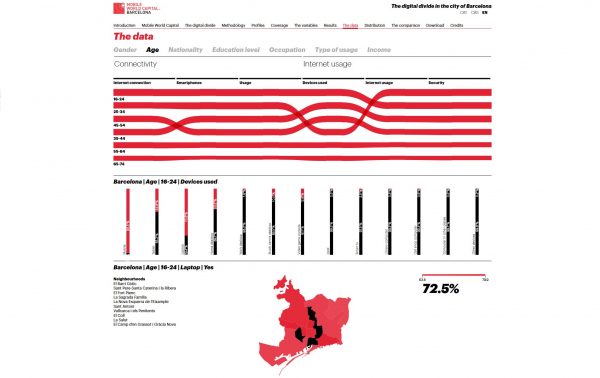

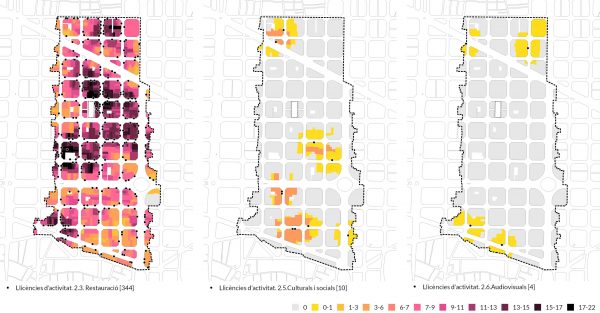

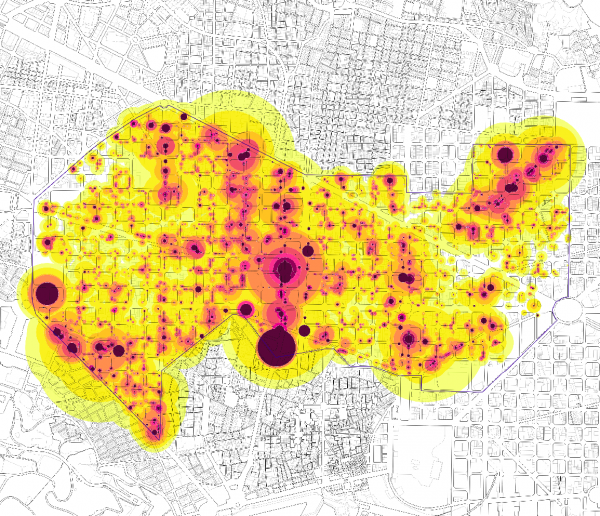

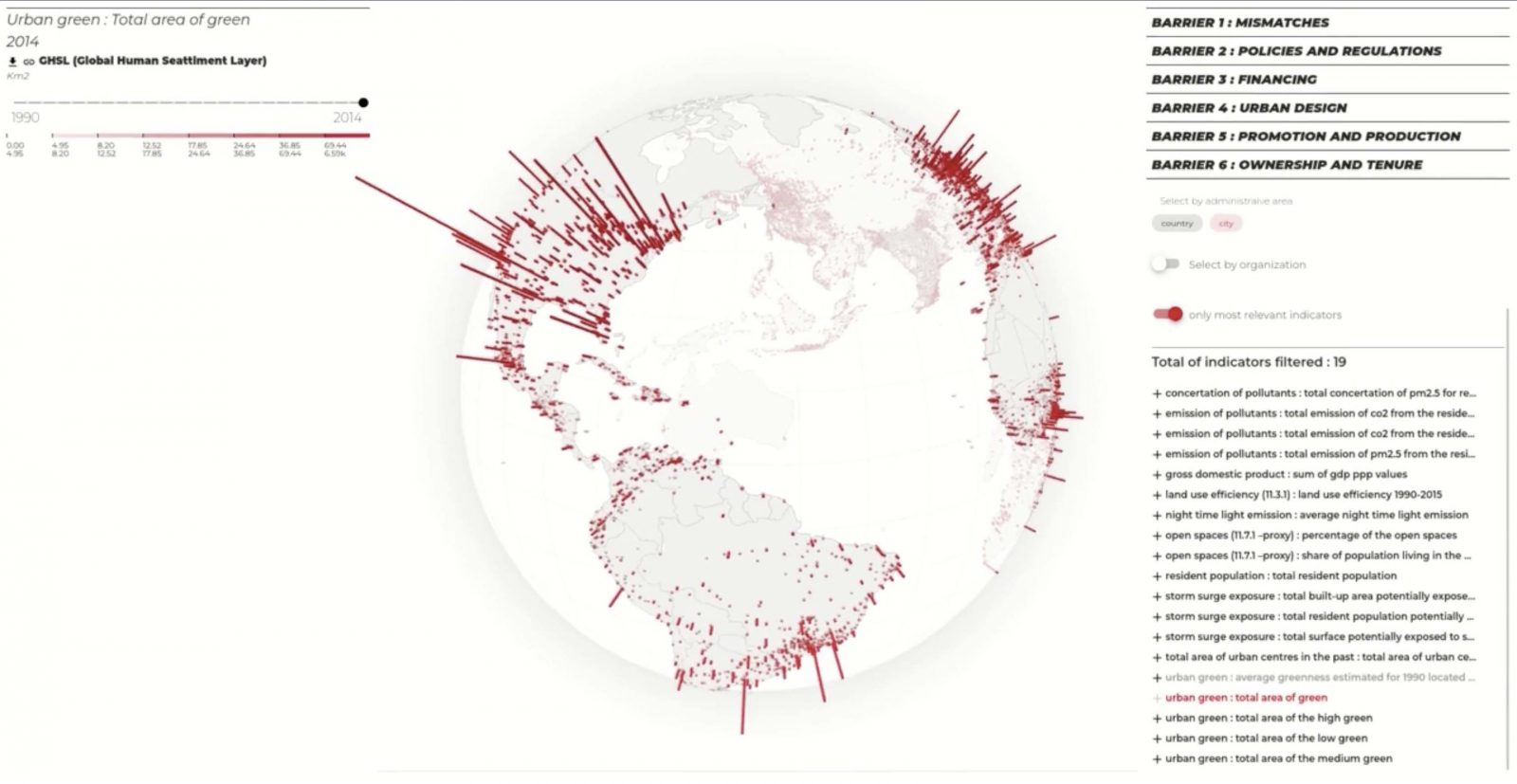

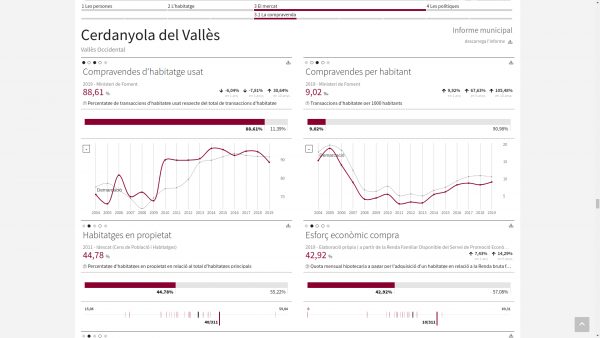

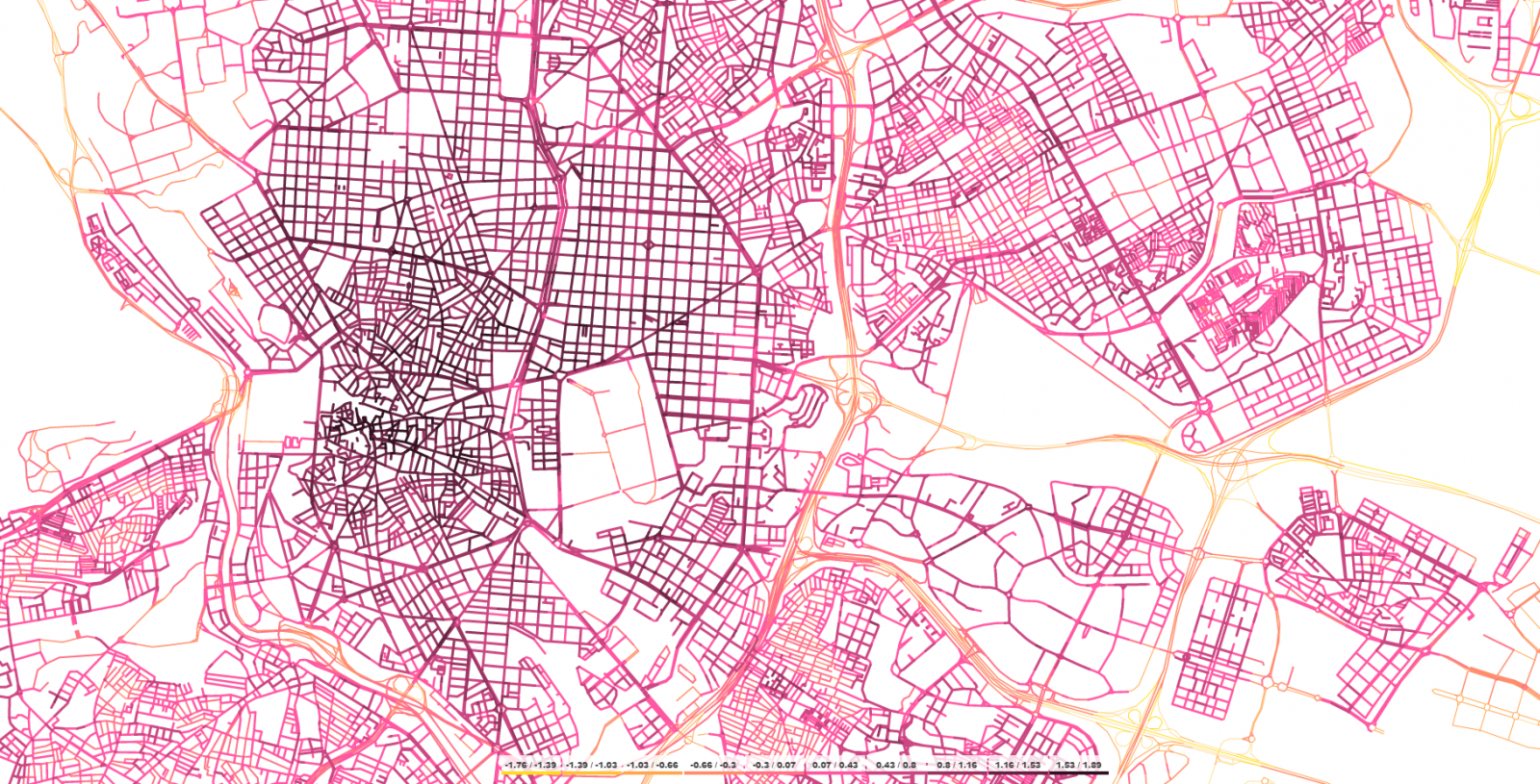

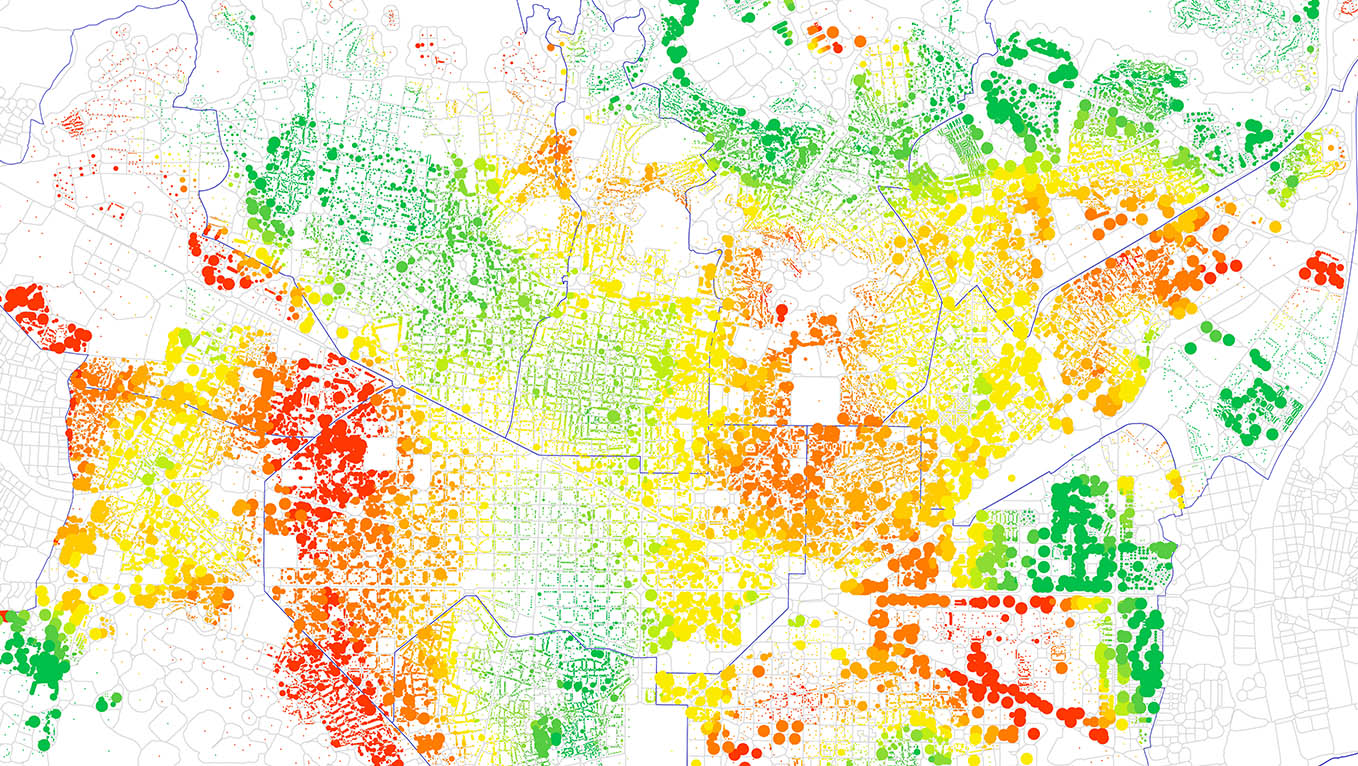

Overall, this transformation needs to be supported by new data-driven knowledge and prospective tools that enable public administrations and decision-makers to deploy the best strategy in the optimal area of the city to achieve social and spatial justice.